Why Some Doctors Are Pushing to End Routine Drug Testing During Childbirth

The request from child welfare authorities seemed harmless enough: Order a newborn drug test. Dr. Sharon Ostfeld-Johns and her hospital colleagues had done it countless times before.

This time, however, the request gave the doctor pause. A patient at Yale New Haven Health in Connecticut, the largest health system in the state, had said that she’d used marijuana to help her eat and sleep during her pregnancy. The hospital had reported her to child welfare authorities. Now, an investigator wanted Ostfeld-Johns to drug test the newborn.

Ostfeld-Johns knew there was no medical reason to test the baby, who was healthy. A drug test would make no difference to the infant’s medical care. Nor did she have concerns that the mother, who had other children at home, was a neglectful parent. The doctor did worry, however, that the drug test could cause other problems for the family. For example, the mother was Black and on Medicaid — race and income bias could influence the investigator’s decision on whether to put the children into foster care.

“Why did I ever order these tests?” Ostfeld-Johns found herself wondering, about past cases. She thought about her own son, then in kindergarten, and how she would feel if she faced an investigation over a positive test. Eventually, she would review her own prenatal records and learn that she had been tested for drugs without her knowledge or consent. “You try to imagine what it would be like if it was you,” she said. “The hurt that we do to people is overwhelming.”

Ostfeld-Johns had encountered this scenario many times before, but this time, she refused the drug test request. Then she began a research process that, in 2022, led to an overhaul of the Yale New Haven Health network’s approach to drug testing newborns. Now, doctors are directed to test only if doing so will inform medical care — a rare occurrence, it turns out. The hospital also created criteria for testing pregnant patients.

Many doctors and nurses across the country have long assumed that drug testing is both a medical and legal necessity in their care of pregnant patients and newborns — even though most state laws do not require it. Yet drug testing during labor is common in America, with a positive test often triggering a report to child welfare authorities. Ostfeld-Johns and Yale New Haven are among a small but increasing number of doctors and institutions across the country that have started questioning those drug-testing policies. This cadre of doctors is pushing hospitals to become less reliant on tests and to focus instead on communicating directly with patients to assess any risks to babies.

No one seems to be tracking just how many hospitals have revised their testing policies, but over the past three years, changes have come to networks across the country, from California to Colorado to Massachusetts. The institutions vary, from large nonprofit networks and teaching facilities to private, for-profit hospitals.

While doctors pushing for reform argue that legislation is still needed to require hospitals to reduce testing, individual hospital efforts seem to be spreading. In Colorado, doctors worked with a child abuse prevention nonprofit to distribute a voluntary new policy as guidance, prompting several hospitals to change their practices. An educational effort, “Doing Right by Birth,” convened virtual groups of health care professionals across the country in 2023, to teach them their requirements under the law. Some participants were surprised to learn that most state laws do not actually require hospitals to drug test pregnant patients or newborns, and are now questioning the policies of their institutions, suggesting more reforms may come.

At Yale, Ostfeld-Johns said she initially faced resistance to the policy change. Some of her colleagues feared that by ending near-automatic testing, “we were ultimately going to hurt babies,” she said. “We were hurting them by preventing identification of substance exposure that happened during pregnancy.” But Ostfeld-Johns said they found they didn’t need the drug tests to identify babies who might, for example, develop symptoms of opioid withdrawal that would require special care.

At the New Haven hospital, the policy change appears to have curbed unnecessary child welfare reports without harming babies. After the policy went into effect, child welfare referrals from the newborn nursery dropped almost 50%, according to preliminary data provided by Ostfeld-Johns. At the same time, the hospital did not see an uptick in babies coming back in need of new treatment for drug withdrawal, she said. “No babies came in with uncontrolled withdrawal symptoms,” she said. “No safety events were identified.”

The New Haven data is consistent with the anecdotal experiences of providers at other institutions. “I don’t think we’re missing babies” who have been exposed to substances, said Dr. Mark Vining, the director of the newborn nursery at UMass Memorial Medical Center near Boston. The hospital did away with automatic testing of newborns in 2024. At the same time, Vining said, it has reported fewer families to child welfare authorities due to positive tests caused by hospital-administered medications, like morphine. A newborn drug test “rarely adds any information that you didn’t already know,” he said.

The new policies are beginning to upend an approach that has existed in the United States for decades.

Hospitals first began routinely drug testing mothers in labor during the 1980s crack cocaine epidemic. The practice expanded during the opioid epidemic, following the passage of a federal law in 2003 and another in 2016, both of which require hospitals to notify child welfare agencies anytime a baby is born “affected by” substances. Federal law and laws in most states do not require hospitals to drug test new parents or their babies, but hospitals frequently do so anyway — often out of concern that if they don’t, they’ll miss babies who are at risk.

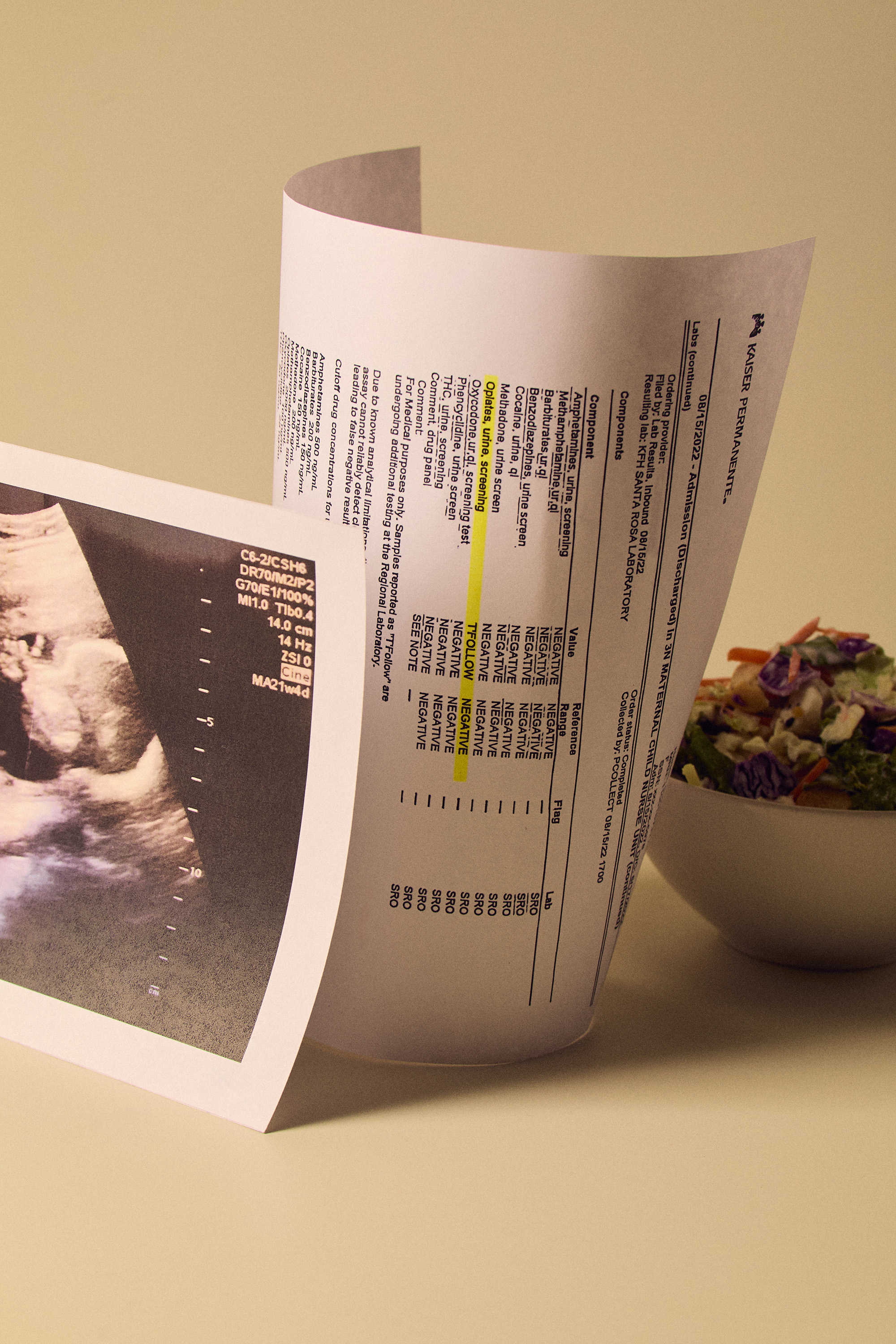

Widespread drug testing has caused a variety of harms. A previous investigation by The Marshall Project found that urine tests, the type used by most hospitals, are easy to misinterpret and have false positive rates as high as 50%. Parents have been reported to child welfare authorities over false positives caused by things ranging from poppy seeds to blood pressure medication. Substances prescribed to patients during a hospital stay, such as the fentanyl in an epidural, can show up on maternal drug tests and also pass quickly from mother to baby, causing infants to test positive for drugs.

Race and class bias can also influence drug testing, with multiple studies finding that low-income, Black, Latina and indigenous women are most likely to be tested. Yale New Haven Hospital found that, before the drug testing policy change, Black babies in its care were twice as likely as White babies to be tested at birth. Studies elsewhere have found that racial disparities extend to child welfare cases and removals as well, with Black, Latino and indigenous babies being less likely to be reunited with their parents once removed.

In many hospitals, the tests are not typically used to make medical decisions. Instead, tests have become a cheap, fast way to assess whether a parent might be a danger to their child.

“We should be doing medical tests for medical reasons, not criminal, punitive, prosecutorial reasons,” said Dr. Christine Gold, a pediatrician who works at the University of Colorado Hospital system near Denver. Even for that purpose, Gold noted, drug tests fall short. “It is a really poor-quality test,” she said. It cannot tell doctors how often someone used a substance during pregnancy, if a patient has an addiction or if the drug use impacted their ability to parent. “Toxicology tests are not parenting tests,” Gold said.

In 2020, Colorado lawmakers removed positive drug tests at birth from the list of reasons for hospitals to automatically report a family to child welfare authorities. But many hospitals continued to test pregnant patients and newborns, prompting Gold to lead the effort to release guidance in 2023 that encourages hospitals in the state to test only when medically necessary. Now the entire University of Colorado Health system is reforming its policy on testing pregnant patients, and others in the state are reportedly considering changes.

Instead of automatic drug tests, the revised policies use screening questionnaires, which collect certain information from patients, such as their family’s history of drug use, and the patient’s own history and frequency of use. Researchers and leading medical groups say these questionnaires are effective at identifying someone with an addiction or at risk of developing one, which can help doctors steer parents into treatment, or determine whether a baby might need extra medical care. Some hospitals continue to drug test patients under certain circumstances. For example, at UMass Memorial, pregnant patients with diagnosed substance use disorders and new patients without any prenatal care are still drug tested.

The growing movement to limit drug testing is a source of optimism for many doctors. But its success hinges in part on doctors building more meaningful relationships with their patients, so the people they treat feel inclined to confide about substance use and ultimately agree to enter treatment. “That is really the goal here,” said Dr. Katherine Campbell, chief of obstetrics at Yale New Haven Hospital. “We’re trying to reduce substance use disorder in reproductive-age people.”

That may include asking a patient for informed consent to submit to a drug test, and medical personnel being transparent about both the purpose of the test and its potential legal consequences.

But these types of conversations can be challenging. They also require longer appointments, something many medical institutions are unable or unwilling to provide. “The system is set up to make it difficult for us to really develop a knowing and trusted relationship with a family,” said Dr. Lauren Oshman, a family physician at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.

By comparison, urine tests are fast and often involve little interaction with patients.

“It takes longer to talk to someone and really understand, than it does to place an order and have the person give a urine sample,” Campbell said.

The new policies also don’t solve other problems. After Oshman and colleagues discovered that clinicians at Michigan Medicine ordered drug tests for Black newborns more often than for White newborns, the hospital network changed its policy in 2023 to require testing of babies only in certain circumstances. But early data indicates the new policy had no impact on the racial disparities in testing and reporting.

One reason, in Oshman’s view, is that Michigan law requires the reporting of a patient whom a provider “knows or suspects” has exposed their newborn to “any amount” of a controlled substance, whether legal or illegal. That includes marijuana, which is legal in Michigan. When the health network team dug into the data, it found that for almost half of all low-risk patients whose babies tested positive, the only drug detected was marijuana, and the patients were most likely to be Black. Most marijuana-only cases do not result in findings of abuse or neglect by child welfare authorities, according to the team’s research. But hospitals are still required to report these patients, Oshman said.

“And that won’t change until the state law changes,” she added.

Hospitals in most other states face similar challenges. A review by The Marshall Project found that at least 27 states explicitly require hospitals to alert child welfare agencies after a positive screen or potential exposure — though not a single state requires confirmation testing before a report.

Many hospitals that have changed their policies are in states that do not require reporting positive tests to child welfare authorities. In both Colorado and Connecticut, for example, hospitals are required to report a parent only if providers have identified other safety concerns. In Connecticut, providers fill out an anonymized form that allows the state to collect data on substance-exposed newborns without requiring a child welfare report.

But even in states that don’t require reporting positive tests, drug testing remains ubiquitous. For example, the New York Department of Health advised hospitals in 2021 to test labor-and-delivery patients only when “medically indicated” and only with their consent. But women continue to report nonconsensual drug testing at hospitals across the state, which has led to them being reported to child welfare authorities over false positive and erroneous results, The Marshall Project has found.

These challenges show that reducing the consequences of drug testing may require a multipronged approach, from legislative reforms to policy revisions to enforcement, experts say.

“We’re just at the beginning,” Oshman said. “This is the start of creating a system that provides that trustworthy care.”

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletters, and follow them on Instagram, TikTok, Reddit and Facebook.